Whether it was her 6’ tall, 200-lb. frame, the lingering aroma of cigars and whiskey or the revolver tucked into her apron waist, any stranger could see that Mary Fields was a force with which they did not want to reckon.

Born into slavery and spending the first three decades of her life in bondage, much is unknown about Mary’s early years, even her birth. Experts estimate that she was born in Hickman County, Tennessee, in 1832. At the conclusion of the Civil War, she was emancipated and secured a job aboard a Mississippi River steamboat. By the 1870s Mary found work as a groundskeeper at the Ursuline Convent in Toledo, Ohio. While her employment at the convent was not without conflict (some didn’t care for her choice of words or her drinking habits outside of work), Mary became close friends with the head nun, Mother Amadeus Dunne.

It is believed that Mother Amadeus was the reason Mary ended up in the western mountains of Montana, the place where she would spend the remainder of her life. Mother Amadeus left the Toledo convent to pursue missionary work in Montana and when she fell ill, it was Mary who decided to make the 1,700-mile journey to help her.

The Ursuline nuns at St. Peter's Mission just outside of Cascade, Montana. Mary Fields pictured with horse and cart on right. (Photo courtesy of Ursuline Centre Archives, Great Falls)

Once there, Mary devoted her working hours to the convent—repairing buildings, establishing a garden, doing laundry and ferrying supplies to the nuns from the nearby town of Cascade. One story goes that while on her way to deliver food to the convent, a pack of wolves spooked her horses and upset the wagon of supplies. All night Mary guarded the provisions with her shotgun until she could make her way to the nuns at daybreak.

After a decade of service, Mary’s employment was ended by the overseeing bishop, who got word of her drinking, smoking and altercations with other hired workers. Things allegedly came to a head when Mary, who had become a construction crew foreman, got into an argument with a worker. The man hit Mary and then pulled his gun on her. She responded by quickly drawing her own revolver, but it is unknown if either of them fired. Mary was forced to look elsewhere to make a life for herself in the sparsely populated frontier.

Looking to support herself, Mary did laundry work and other odd jobs around the town of Cascade. In 1895, Mother Amadeus, who was still friends with Mary, helped to land her a contract to deliver mail. According to the Smithsonian’s Post Office Museum, “A Star Route Carrier was an independent contractor who used a stagecoach to deliver the mail in the harsh weather of northern Montana. Mary was the first African-American woman and the second woman to receive a Star Route contract from the United States Post Office Department.” Though she was over 60 years old, the legend of “Stagecoach Mary” was born.

In 1895 Mary Fields became a Star Route Carrier, delivering mail for the United States Post Office Department. (Photo courtesy of Ursuline Centre Archives, Great Falls)

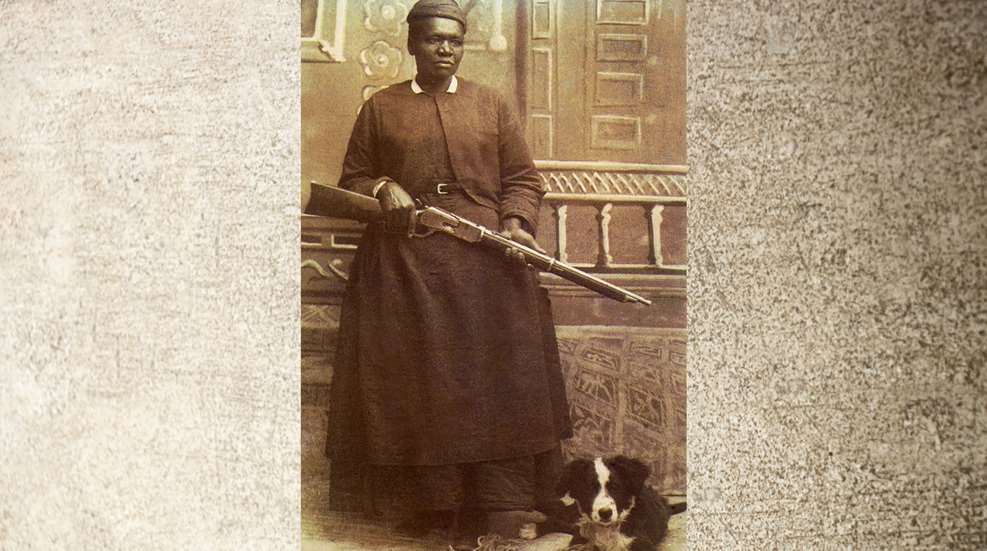

Managing a horse team and wagon, paired with the harsh Montana weather and any other threats that loomed along the route, was no easy task, but Mary was already a seasoned candidate for the job. Her “everyday carry” was a Smith & Wesson .38 double-action revolver (reputedly a Safety Hammerless “Lemon Squeezer”). The most iconic image of Mary shows her holding a Winchester 1876 saddle ring carbine (likely a studio prop). In a more candid photograph of her, possibly from the 1890s, Mary shoulders a double-barreled shotgun, a more likely armament of a stage driver and frontierswoman.

True to the unofficial Postal Service motto, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds,” Mary took her job seriously. Dressed in a man’s jacket and hat over her apron and skirt to keep warm against the cold weather, she struck an imposing figure seated high on the coach. When winter snows proved impassible for her horses, she carried the mail on foot to their recipients. She became known in the town of Cascade as an independent and pioneering woman of her time.

After eight years as a mail carrier, Mary retired from her route and started providing laundry and childcare services in Cascade. One day she baby sat a little boy who was visiting from out of town. He remembered the stories she entertained him with for the rest of his life.

“She smoked cigars until the day she died,” film icon Gary Cooper, a Montana native himself, recalled of Mary Fields in a 1959 article in Ebony magazine. “They say [she] could whip any two men in the territory. She wore a .38 Smith and Wesson strapped under her apron and they swear she couldn’t miss a thing within 50 paces.”

In 1914, at the age of 82, Mary died. As with many iconic figures, the dividing line between the myth and reality of her incredible life is not always clear. Characters based on her have appeared in Western movies and television shows, including the recent AMC series “Hell on Wheels.” But one fact is echoed by all who knew her—she had a strong will that allowed her to survive in a time of tumultuous change in the American West.

Cooper may have summed her up best. “Born a slave … Mary lived to become one of the freest souls ever to draw a breath or a .38."

Above right: Mary with her double-barreled shotgun, wears a man’s jacket and hat in the cold Montana climate. Public Domain image.