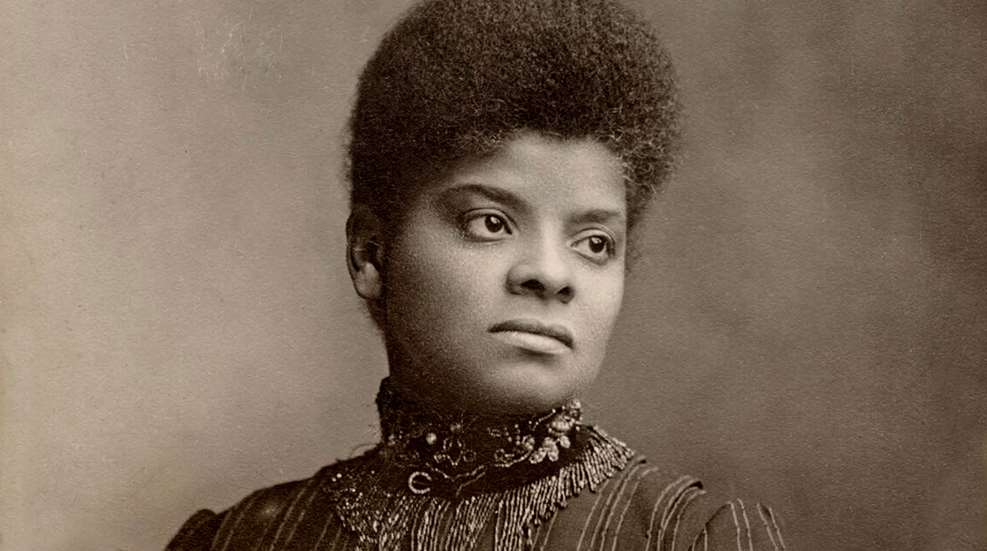

Ida B. Wells wore many hats—educator, journalist, activist, mother—but no matter what she put her hand to, she pursued it with unwavering determination. Born in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, the oldest of eight siblings, she spent the first three years of her life in slavery. After the Civil War, her father started a carpentry business and became politically active in the Republican party during Reconstruction.

Ida’s early education started at Rust College in Holly Springs, until a yellow fever epidemic claimed the lives of both her parents and a brother in 1878. At age 16, Ida was determined not to allow the rest of her family to be split up amongst relatives, and found a job teaching at an elementary school to support her siblings. Several years later, the Wells children moved to Memphis to live with an aunt.

While juggling college classes and her job as a teacher, Ida was thrust into a legal battle over an incident that occurred while she was riding a train in the city. Ida had purchased a ticket to ride on the first-class car but, as the law allowed train companies to segregate passengers, she was told to move to a different car. She refused and was physically removed from the train. A Tennessee State Museum article details Ida’s legal fight against the company, which ended in a settlement.

Two years later, the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned Ida’s victory, but she already had a taste for fighting for justice. Ida began to rely on the First Amendment, specifically the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press, to bring attention to African American civil rights issues. Beginning to write for African American newspapers using the byline “Iola,” Ida soon became editor, then co-owner of the Memphis paper The Free Speech and Headlight. Her job as an educator was terminated after she published her criticisms of the conditions of the segregated schools in which she taught.

It was in 1892 that Ida began to exercise her Second Amendment rights, after Thomas Moss, who was a close friend, was killed by a lynch mob. It was a racially fueled incident that originally stemmed from an argument over a game of marbles, then escalated into a neighborhood fight in southern Memphis. The employees of two competing grocery stores across the street from each other became involved in the physical fight. Later, when a group of supporters of the white-owned store arrived to attack Moss’ store, they were met with defensive gunfire. While several of the attackers sustained injuries, Moss and his employees were jailed, awaiting trial. As newspaper headlines spread fear of retaliation by the African American community, a mob of 75 masked men descended on the jail, dragged the three men from their cells, took them to a railyard and murdered them. Before being shot, Moss implored, "Tell my people to go west, there is no justice here."

Ida details how her friend’s lynching convinced her of her need for protection in her memoir Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells:

"I had bought a pistol, the first thing after Tom Moss was lynched, because I expected some cowardly retaliation from the lynchers. I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or rat in a trap. I had already determined to sell my life as dearly as possible if attacked. I felt if I could take one lyncher with me, this would even up the score a little bit."

Ida’s perceived need to arm herself was well justified. Two months later, retaliation did occur in response to her continued publishing of anti-lynching articles. The office of The Free Speech and Headlight was attacked and ransacked while she was out of town.

Ida’s life story highlights the history of the use of firearms for self-defense in the African American community, a story clearly outlined by Nicholas Johnson in his book Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms. Some of the earliest "gun control" laws in this country were aimed at keeping African Americans, both enslaved and free, from bearing arms. Despite this, slaves armed themselves in several famous revolts.

Escaped slaves also often found that firearms were the difference between freedom and re-capture. In his book, The Underground Railroad, William Still details several incidents where they used their firearms effectively, including one in 1855 where two escaped slave couples were stopped while making their way to freedom:

"At this juncture, the fugitives verily believing that the time had arrived for the practical use of their pistols and dirks, pulled them out of their concealment—the young women as well as the young men—and declared they would not be "taken!" One of the white men raised his gun, pointing the muzzle directly towards one of the young women, with the threat that he would "shoot," etc. "Shoot! shoot!! shoot!!!" she exclaimed, with a double barrelled pistol in one hand and a long dirk knife in the other, utterly unterrified and fully ready for a death struggle. The male leader of the fugitives by this time had "pulled back the hammers" of his "pistols," and was about to fire! Their adversaries seeing the weapons, and the unflinching determination on the part of the runaways to stand their ground, "spill blood, kill, or die," rather than be "taken," very prudently "sidled over to the other side of the road," leaving at least four of the victors to travel on their way."

In William Still's "The Underground Railroad" he details an 1855 incident of escaped slaves using firearms for self-defense. (Library of Congress image)

During the Civil War, roughly 200,000 African Americans fought for the Union Army and Navy; 40,000 died; and 16 won the Congressional Medal of Honor. “Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman, who scouted for the Second South Carolina Volunteers”, according to the National Archives. These men and women were trained to shoot and maintain their firearms. After the war, many ex-soldiers and former slaves saw firearm ownership as essential to maintaining their freedom and protecting their homesteads. Many became law enforcement officers. As Reconstruction ended, however, laws restricting firearm ownership by African Americans returned to the books.

A woodcut of Harriet Tubman from her time serving in the Civil War. Tubman served under the Union Army with the African American regiment, the Second South Carolina Volunteers.

In 1892, her newspaper destroyed, and her life threatened should she return to Memphis, Ida made New York City her new base for the next several years to continue her anti-lynching campaign. She published several pamphlets, and even traveled to Great Britain to lecture on the subject. In her publication Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases Ida points out:

“Of the many inhuman outrages of this present year [1892], the only case where the proposed lynching did not occur, was where the men armed themselves in Jacksonville, Fla., and Paducah, Ky, and prevented it. The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense.

The lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well, is that a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

In the context of the late 19th century, the term “Winchester” was synonymous with a reliable and affordable repeating rifle, a “modern sporting rifle,” if you will. At the time, a lever-action Winchester-type rifle was cutting-edge technology. (It wasn’t until 1893, that the U.S. Army adopted its first smokeless powder repeating rifle to replace its single-shot Trapdoor Springfields.) In the hands of an individual facing down a mob, a “Winchester” was a “force multiplier.”

An ad for an 1873 Winchester rifle (courtesy Winchester Repeating Arms)

In 1895 Ida married attorney and journalist Ferdinand Barnett, with whom she had four children. Following her marriage, she referred to herself as Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Her husband had previously established Chicago’s first African American newspaper in 1878, The Chicago Conservator, where Ida later became editor and owner of the publication. Her writings drew the attention and praise of abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, and in 1909 she helped establish the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Chicago would become Ida’s home for the rest of her life.

Eventually, Ida’s activism would include women’s rights as well. Looking to join the women’s suffrage movement, she was met with animosity. She was told her campaign for African American women’s rights alongside white women’s rights would detract from the movement. At a suffrage parade in Washington D.C. in 1913, before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, she was told by organizers not to march with her state’s delegation, but instead to move to the back of the parade and join the group of African American marchers at the rear. Again, she refused. Ida proceeded to position herself amongst fellow Illinois white suffragists and marched peacefully down the route. Ida sought political office later in life, running for a delegate spot in the Republican National Convention in 1928 and seeking an Illinois Senate seat as an Independent in 1930, but lost both races.

Campaign material for Ida B. Wells-Barnett from 1928 (Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Ida died in 1931. Her legacy was carried on into the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, including the principle of the use of firearms for self-defense. Leaders in the civil rights era clearly established the difference between political nonviolence and the right of self-defense. Rejecting the use of violence to obtain political ends did not mean giving up the right to defend oneself against aggression.

This story is highlighted in Johnson’s book and is eloquently told in Charles E. Cobb’s book This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made The Civil Rights Movement Possible. The book’s title paraphrases a quote from Mississippi civil rights activist Hartman Turnbow. Turnbow also explained his use of firearms when attackers tried to burn down his house by saying, “I wasn’t being non-nonviolent, I was just protectin’ my family.” He was joined by other civil rights activists, like Fannie Lou Hamer, who declared, “I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom…”

While Martin Luther King Jr., who was famously denied a concealed carry permit, successfully led thousands of followers with his example of passive resistance, he was often protected by armed volunteers. In his 1959 essay “The Social Organization of Nonviolence”, King observed:

“…violence exercised merely in self-defense, all societies, from the most primitive to the most cultured and civilized, accept as moral and legal. The principle of self-defense, even involving weapons and bloodshed, has never been condemned … When the Negro uses force in self-defense he does not forfeit support—he may even win it, by the courage and self-respect it reflects.”

Ida B. Wells and her legacy are preserved in books, plays, foundations and museums. Throughout her life, she fought for the rights she knew should not be denied her, as an African American and as a woman, using words both spoken and written, and was prepared to take action to defend those rights. She understood, almost 140 years ago, that in order to defend your freedoms you must be able to defend yourself ... and that the First and Second Amendment go hand-in-hand.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett marches in the 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade in Washington D.C. (Chicago Tribune).