When discussing the use of the .22 LR rifle cartridge for self defense, I've previously stated (on more than one occasion) that there are no cartridges designed specifically for that purpose. It's not too hard to find a variety of reliable premium-grade sporting loads or small game hunting rounds that can be pressed into service. Although defensive .22 Magnum loads have been around for some time, there hasn't been anything specifically marketed for use in .22 LR handguns.

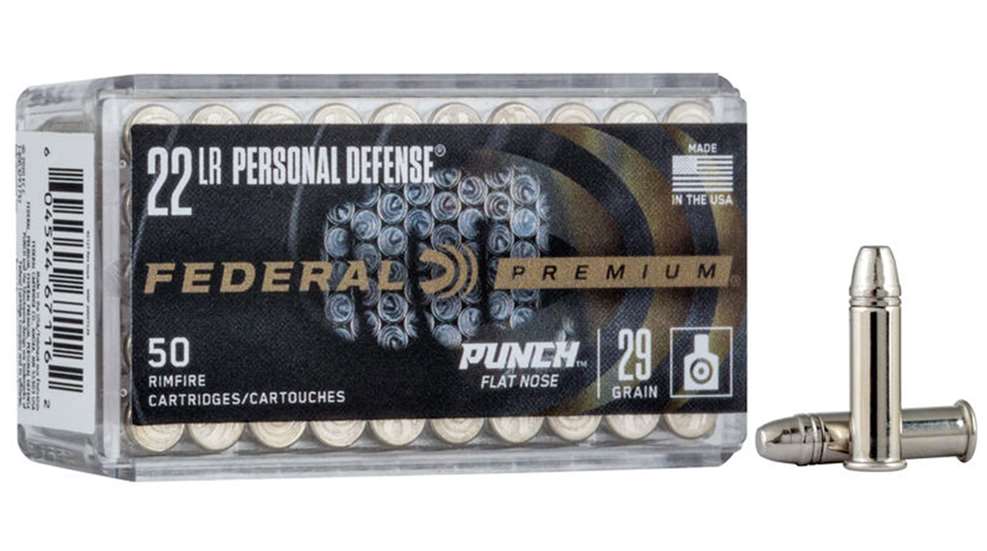

This changed in 2021 when Federal Premium Ammunition expanded its Punch Personal Defense ammunition line-up to include a .22 LR cartridge.

The performance data on the side of the Federal Punch .22 LR box was generated using a 2” barrel. Most .22 LR ammunition is made for use in use rifle-length barrels.

The Punch series represents a different direction for Federal, which has focused primarily on developing ammunition to meet the needs of law enforcement personnel for the past three decades. However, the likelihood that a civilian self-defender will have to concern himself with carrying ammunition that can satisfy stringent FBI testing protocols (like shooting through automotive glass) are relatively low. Instead, folks out of uniform are more likely to encounter assailants in face-to-face situations at relatively short distances.

Taking advantage of the extensive amount of data gleaned from decades of law enforcement ammunition development, Federal tuned Punch ammunition to be a better fit for real-world daily carry. The company recognized that in addressing the needs of everyday people that they would need to include some calibers that fall outside of police preferences, like the .22 LR.

How effective a given cartridge can be for self-defense has a good deal to do with bullet design. The 9 mm pistol cartridge went from being rejected as ineffective by the FBI in the 1980s to then being re-adopted by that agency in the 2010s. This change in policy is due in no small part to ammunition manufacturers developing more effective 9 mm bullets that have trickled down into the civilian marketplace.

The Ruger LCP II Lite Rack is representative of the small rimfire pistols for which the Punch load was designed.

But the .22 LR is not a 9 mm pistol cartridge. With commercial bullet weights ranging from 20 grain to 60 grain, this rimfire cartridge lacks the bullet mass needed to behave like a 115-gr. to 147-gr. bullet fired from a larger centerfire cartridge. Just a reminder that, in most cases, manufacturers are looking for two positive bullet performance characteristics in defense-grade ammunition: penetration and expansion. FBI bullet testing guidelines indicate that those bullets which travel to a depth of 12 to 18 inches in blocks of 10 percent ballistic gelatin are most likely to provide enough penetration in a real-life situation to be effective in stopping a threat.

Bullets that expand as they travel through the gelatin (hollow-point bullets in most cases) have two added benefits. First, they crush and destroy more tissue along the way. Secondly, the expanding tip acts a bit like a parachute. It slows the bullet down so as to make it less likely to over penetrate the intended target and cause unintended collateral damage. Of the two bullet performance characteristics, penetration trumps expansion. Regardless of how a bullet behaves along the way, if it doesn't travel deeply enough to strike vital tissues then it won't fulfill its intended purpose.

A typical 36-gr. copper-plated sporting hollow point .22 LR bullet lLeft) shown next to the nickel-plated 29-gr. jacketed flat-nose Federal Punch bullet.

Plenty of .22 LR cartridges are topped with expanding hollow point bullets. However, these hollow points are not ideal for defense. Generally these small bullets need to be traveling at rifle-level velocities in order to expand properly. So technically speaking, their performance can be inconsistent depending on the gun used. From rifles they act like hollow points, while from handguns they act like non-expanding bullets. Additionally, due to its relatively low bullet mass, .22 LR tends to underpenetrate when fired from handguns, which means an expanding hollow point would likely reduce penetration even more.

With these considerations in mind, Federal honed in on the .22 LR bullet characteristics that could be improved upon. Dan Compton, Federal’s manager of shotshell and rimfire ammunition says, “We set out to prove that a .22 bullet could penetrate between 12 and 18 inches, and we accomplished our goal.” They did so by giving the Punch cartridge a 29-gr. lead core bullet with a heavy nickel jacket. The light bullet weight allows it to travel faster while the jacket intentionally minimizes expansion and retains bullet weight to keep it moving in a straight line. Flattening the nose of the bullet (i.e. the meplat of the bullet) causes greater tissue disruption than a rounded nose. This is a significant bullet redesign which is one of the reasons other ammunition makers have swerved around developing a defensive .22 LR load.

Shown here is one of 10 percent ballistic gelatin blocks used by Federal’s for in-house performance testing. It shows a listed bullet penetration depth of 13.75".

The Punch .22's cartridge case is also nickel-plated, which gives the case increased corrosion resistance. But the primary reason for the nickel is to give it a slicker surface for improved cycling in small semi-automatic pistols, which tend to be among the most finicky feeders in the handgun world. Smokeless gun powder has been finely tuned over the years to produce formulations suited to particular types of guns. Usually .22 LR cartridges contain powder charges developed for 16” or longer rifle barrels. Firing those rounds through much shorter pistol barrels results in significant drops in bullet velocity.

Federal optimized the .22 LR Punch load for use in handguns with a listed maximum velocity of 1,070-fps. for 74 ft.-lbs. of energy at the muzzle when fired from a 2” pistol barrel. Federal also lists a maximum 24” barrel rifle velocity of 1,650 f.p.s. (which is fairly fast for this caliber) for 175 ft.-lbs. of energy. Since most pistols have barrels longer than 2 inches and rifles tend to be shorter than 24 inches, the real-world performance numbers lie somewhere in between.

This cartridge performed reliably in the pistol, revolver and semi-automatic carbine used for the range test.

To find out, I took a few boxes of Punch .22 to the range with three test guns. In the pocket pistol category was the Ruger LCP II Lite Rack. Pitching for the carbine-size semi-automatic rifles was a Magnum Research SwitchBolt (similar to the Ruger 10/22) with a 17” barrel. Rounding out the test set was the 4.62” barrel Ruger Wrangler which comfortably covered the revolver and “whatchagot” categories. Here are the velocity numbers for 10-rounds fired next to a Lab Radar chronograph:

Firearm: Barrel: Muzzle Velocity: Muzzle Energy:

Ruger LCP II 2.75" 1107 f.p.s. 79 ft.-lbs.

MRI Switchbolt 17" 1556 f.p.s. 156 ft.-lbs.

Ruger Wrangler 4.62" 1287 f.p.s. 107 ft.-lbs.

I chose these three guns because I've conducted thorough range tests with them in the past. So I had a good idea of what to expect in regards to reliability and accuracy. The Punch .22 Fed, fired and ejected properly from all three models without any issues or problems. That included some rapid-fire testing with the semi-autos. Accuracy testing was fairly limited. But group sizes were right in line with the accuracy results these guns produced with other premium loads.

Just to be clear, I'm going to continue to stand by the general consensus that .22 LR pistols are not an optimal choice for concealed carry or home defense. Handguns chambered in .380 ACP or larger calibers offer better performance than a .22 LR, if you can manage the recoil and practice with them regularly. But for those who do choose to stage a .22 for personal protection, the Federal Punch .22 round is purpose built for the job and up to the task.

For more information, visit federalpremium.com.