Have you ever sat around the dinner table at night complaining about not paying enough taxes, wishing your representative government would impose more taxes than is already being squeezed out of your paycheck? Have you ever demanded that your congressional representative meet with you so he or she could come up with a new way of taxing his or her constituents?

This is exactly what happened in the early 1930s. A group of sportsmen approached their senators and congressmen with their concerns that if there was no money for conservation, sportsmen might run out of huntable species. In 1937, Nevada Senator Key Pittman and Virginia Senator Absalom Willis Robertson penned the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (16 U.S.C.A. 669 et seq).

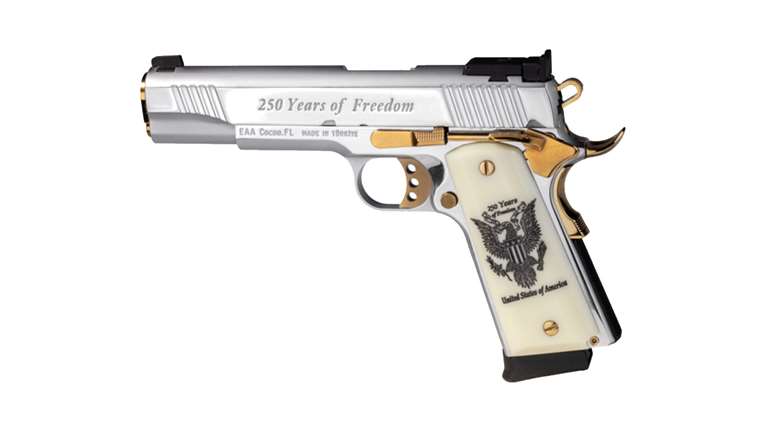

Known as the Pittman-Robertson Act, signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt, it imposed an 11 percent federal excise tax on firearms, ammunition and archery equipment to be redistributed back to the states for wildlife restoration and conservation projects. The Pittman-Robertson Act was enacted to address the problem of species being pushed to the brink of extinction due to market and commercial hunting and loss of habitat due to human encroachment.

The success of the Pittman-Robertson Act is because the funds collected do not get deposited into the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury, but rather are entrusted with the Secretary of the Interior and earmarked for the restoration, conservation and other issues of interest to hunters and wildlife managers. The Secretary of the Interior then re-distributes these funds according to a formula that is based on the number of licensed hunters in each state. Each state must meet certain requirements and the funds must be spent on approved options and projects and include but not limited to research, surveys, acquisition or the leasing of land.

The Act has been amended several times since it's signing into law. With the passage of the Dingell-Hart Amendment in 1972 and the original Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937, funding from federal excise taxes on handguns and archery equipment was made available to states to fund hunter safety education and target range development projects. For example, in 2019 Texas received $30,946,041 with $3.8 million going to the state’s Hunter Education Program. If there are any unused funds by the states or U.S. territories after two years, they are reallocated to the Migratory Bird Conservation Act.

The Pittman-Robertson Act allows funds to be collected through federal excise taxes. Excise taxes are imposed at the time of manufacture or importation. In other words, it is a built-in tax not to be confused with a sales tax at the time of purchase by the consumer. Many products such as firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment for example are taxed twice—once at the time of manufacture or importation and another at the time of purchase by the consumer, usually in the form of a sales tax.

The rate of excise tax imposed by the current Pittman-Robertson Act is as follows:

- Handguns — 10% of Wholesale Price

- Other Firearms such as rifles, carbines, machine guns, shotguns and antique — 11%

- Cartridges and shells — 11%

- Firearms Parts and accessories — 11%

- Archery Equipment — 11%

The collection of total funds varies from year to year for these categories. The average collection from each category is as follows:

- Handguns — 25%

- Other Firearms — 32%

- Ammunition — 34%

- Archery Equipment — 9%

In fiscal year 2022, the Pittman-Robertson Act allocated $1.1 billion to the states and territories of the U.S. Wildlife restoration programs get the largest share of the funds. Land acquisitions and habitat improvement has led to some species such as bear, elk, whitetail deer and mountain lions increasing their range. This has led to more hunting opportunities for those engaged in the sport. The Pittman-Robertson Act has been a win-win for sport hunting in the United States. Not only does this benefit game animals, acquisition and improvements of these lands also benefit non-game species and songbirds, all of which take advantage of improved habitats. Thus even the non-hunter can enjoy the benefits of the Pittman-Robertson Act.

The successes of the Pittman-Robertson Act are highly visible. The success is measurable in terms of wildlife populations. Species such as the American alligator have a larger population now than their numbers in 1900. Many other species, such as the bald eagle, have been removed from the Threatened and Endanger Species list. Other species often cited as successes of the Pittman-Robertson Act are the pronghorn antelope, wild turkey, whitetail deer and elk.

In the 1930s, there were about 12,000 pronghorn antelope, 30,000 wild turkey, 500,000 whitetail deer and 41,000 elk in the United States. Since the passage of the Pittman-Robertson Act, the pronghorn antelope population has increased to 1.1 million; the wild turkey population has increased to 7 million; the whitetail deer population has increased to 18 million; and the elk population has increased to 800,000. These numbers are why most sportsmen and women are not opposed to paying the federal excise tax associated with the Pittman-Robertson Act.

It is a truth that hunters pay for conservation in America, accomplished through hunting license sales, stamps and endorsements. Unfortunately, these things barely scratch the surface to pay for the operations of the various state game and fish departments. It is the funds generated through the Pittman-Robertson Act that directly benefit wildlife populations, habitat acquisition, and utilization by sportsmen and women.

Hunting is a part of our American heritage, passed down by families to future generations. And for those who did not grow up in a family that hunts, the Pittman-Robertson Act provides the funds to educate those new to hunting so he or she can create new family traditions and values.