Henry Repeating Arms is an American gun manufacturer best known for building old-fashioned lever-action rifles and carbines. Nevertheless, they have been plowing plenty of new ground recently. Early in 2023, Henry stepped all the way into a new firearm category with the launch of the Henry Homesteader, a semi-automatic 9 mm carbine that feeds from popular pistol magazines. It was also the first to offer lever guns chambered in the brand new Remington .360 Buckhammer straight-walled rifle cartridge. But the year held one more surprise.

The Big Boy Revolvers blued steel, polished brass and hardwood grips fit right in with Henry’s lever actions like the Golden Boy .22 Mag.

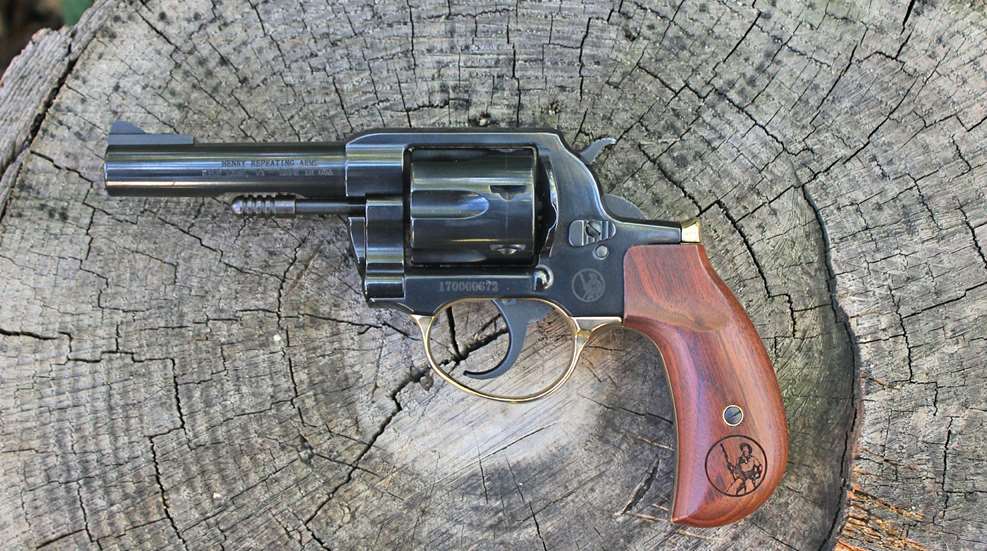

At the 2023 NRA Annual Meetings & Exhibits in Indianapolis, Henry launched the company's very first handgun action platform, the Big Boy Revolver. The first models out the door was a pair of .357 Mag. six shots with a choice of either a square-butt gunfighter grip or a birdshead grip frame. Here is a closer look at the birdshead version.

Technically speaking, the Big Boy revolvers are not Henry's first handgun. For many years the company has offered rimfire and center-fire Mare's Leg pistols. These are lever-action handguns, assembled at the factory with cut down grips and barrels, fashioned after the gun carried by actor Steve McQueen in the TV series “Wanted Dead or Alive” (1958). But this revolver qualifies as the first “bona fide” handgun action to bear the Henry logo.

The barrel features a fixed blade front sight and a shallow cutout for the rounded head of the ejector rod.

The Big Boy is a medium sized frame double-action revolver which borrows from a variety of design influences. The goal was not to reproduce an existing platform but to create something unique that fits in comfortably alongside the Old West feel of Henry's blued steel, brass receiver and hardwood stocked long gun offerings. The result is a revolver with classic design sensibilities neatly blended with the durability and safe operations of modern double-action revolver construction. In short, it's a Henry!

The rear trench sight ends in a square notch which is milled directly into the top strap of the receiver.

The majority of the revolver is constructed from polished carbon steel with a handsome blued finish. This includes the barrel, cylinder and the receiver. The exception to this is the brass grip frame which has been polished to a mirror shine. The sighting system consists of a fixed narrow blade up front paired with a groove milled into the receiver's top strap which ends with a milled-in square notch that serves as the rear sight. The heavy, 4" long round-profile barrel is un-tapered with the caliber stamped on the right side and the company information stamped on the left.

Like many early double-action revolvers, including the Colt Police Positive, the Big Boy's ejector rod is not covered by a barrel shroud. But there is a shallow cutout along the bottom edge of the barrel to accommodate the rounded and grooved ejector rod head. This allows the rod to rest up close to the barrel to greatly reduce the chance of it snagging while making this gun easier to holster.

The Big Boy can be fired with ammunition ranging from soft shooting target .38 Spl. loads all the way up to full power .357 Mag. hunting rounds.

The 6-shot cylinder rotates counterclockwise and swings out to the left side of the frame in typical double-action revolver fashion. The left side cylinder release is of the push-forward variety, like those found on Charter Arms, Smith & Wesson and Taurus revolvers. Although the shape of the release is unique, it leans more towards the vintage Charter Arms shape than anything else.

The steel trigger is deeply curved with a smooth face. It works in conjunction with a spurred hammer which is deeply grooved for improved purchase. This allows the revolver to be fired in double-action (uncocked) or single-action (manually cocked) modes.

The Big Boy is a medium-frame revolver comparable in size and price to guns like the Ruger GP100 and the Smith & Wesson Model 19.

Firing double-action is faster but comes with a trigger travel distance of 1" and trigger pull of 9 lbs. 10 oz. That's an improvement over many revolvers in this class which have double-action triggers in the 12- to 15-lb. range. Cocking the hammer before firing takes a bit more time but it reduces the trigger stroke to an impressively short 1/16" and drops the trigger pull weight to 3 lbs. 12 oz. In either mode, the trigger is exceptionally smooth and clean. For a first-time revolver builder, Henry has nailed the premium trigger feel right out of the gate.

The main spring and grip panels are supported by an internal steel extension.

The one-piece polished brass grip frame features an integral, rounded trigger guard. The smooth, rounded American walnut grip panels are laser engraved with the Henry logo. The panels are secured by short left and right-side screws instead of a long, single screw that passes through both.

Removing the panels reveals a clever mechanical solution to the limitations of installing a brass grip frame. No matter the alloy used, brass is simply not as hard as forged steel. This makes it less than ideal for supporting moving parts like the mainspring assembly which powers the hammer. Henry engineers designed the Big Boy with a steel frame which extends from the receiver down into the grip frame. Much like the grip post of a Ruger GP100, this extension houses the mainspring assembly and the grip panel screws to eliminate those sources of stress to the brass of the grip frame.

The Big Boy revolver chambered, fired and ejected all ammunition tested without any issues.

This version of the Big Boy tips the scales at 33.5 oz., unloaded. The fit and finish proved to be top-notch throughout. The bluing was deep and even, the controls and action buttery smooth in their operations and the walnut grip panels tightly and precisely fitted to the grip frame. For those who want to dress this revolver up even more, Henry offers additional grips, including a striking solid cocobolo wood set, and the field-ready Diamond D Leather Alaskan Hip Holster (HAHHR4).

At the shooting range, the Big Boy proved to be utterly reliable with all ammunition tested. The sight configuration is useful and has the benefits of being rugged and snag-free but it is more rudimentary than some options. The trigger felt like it had been treated to an action job by a custom work gunsmith, not like a trigger off a production line. Formal accuracy testing at 15 yards went smoothly using .38 Special, .38 Special +P and .357 Mag. loads provided by Federal Premium, Hornady and SIG Sauer. Here are the results:

The cherry on top of the Big Boy sundae was the birdshead grip frame. It does not have a continuous backstrap curve, from top to bottom, like most birdshead-gripped models in production today. Instead, the top of the backstrap drops straight down for about half an inch, like a gunfighter grip, before curving out. I had come to think of this style of grip as a “Pinkerton Birdshead” because I saw it for the first time attached to the Hartford Pinkerton Model of 1873. My sources at the NRA tell me it’s most likely called a Thunderer birdshead configuration. So, I’ll stick with that.

I've shot a good number of .357 Mag. revolvers with standard grip shapes and I'll be the first to admit that they can be fatiguing and even uncomfortable when firing full-power ammunition. The top of the grip can feel like a karate chop to the web of the shooting hand thumb after a while.

Henry offers additional grip options for these revolvers, including the solid cocobolo wood grips shown here (right) next to the fact installed walnut grips (left).

But Henry's interpretation of the Thunderer grip is almost magical. The curvature of the grip's backstrap distributes the recoil across the palm of the shooting hand just a moment before the top of the grip reaches the web of the thumb. When it does arrive, the grip starts to roll back in the hand to help mitigate the recoil even more. I was expecting this mid-size wheel gun to give me a workout like other models I've tested. It's still a handful with hot loads but the birdshead grip dynamic made the Big Boy one of the most comfortable and least fatiguing .357 Mag. revolvers I've worked with so far. I can't promise the grip will fit every hand shape this well, but it certainly worked for me!

The Diamond D Leather Alaskan hip holster comes with an adjustable belt loop that can be fitted to belts or backpacks.

When some gun manufacturers step into a new-to-the-company facet of the shooting market, the fact that they are still finding their production sea legs is apparent in the early models that come off the assembly line. These guns work well enough to be sold but future models show noticeable refinements of various features. However, this is not the case with the Henry Big Boy revolver. Based on the time spent with the gun I received, I would have assumed it came from a company that's been making revolvers for many years and that this one received an in-house action job.

The Big Boy's suggested retail price of $928 might seem a bit high to some readers. But it’s $40 to $50 less than the list price of a Smith & Wesson Model 19 Classic or a blued steel Ruger GP100. The Big Boy's real-world prices are lower currently hovering around $799. Once again, Henry provides a premium action and finish at a more affordable price. I'm looking forward to seeing what they come up with next!

For more information, visit henryusa.com.