The Sicily–Rome American Cemetery and Memorial is neither in Sicily nor in Rome, but rather it is situated on the northern outskirts of the city of Nettuno on Italy’s west coast. It is so named because it is the final resting place for nearly 8,000 Americans who lost their lives during the liberation of Sicily in 1943, and the campaign to liberate the city of Rome that began soon thereafter with the Allied amphibious landings at Salerno.

When the battle north of the Volturno River stalled in the Liri Valley shortly before Christmas of that year, an amphibious landing operation called SHINGLE was planned, which ultimately brought an Anglo-American assault force ashore at Anzio on Jan. 22, 1944. The first bodies were buried here two days later. In 1956, it was officially dedicated as a permanent place of burial, with 7,845 headstones covering a 77-acre site that is just as meticulously maintained today as it was 66 years ago when it was first consecrated. A wide central mall leads visitors from an elliptical reflecting pool past 10 grave plots (lettered A through J) to the memorial itself, which features a statue of a soldier and a sailor on a simple stone plinth in the middle of a columned peristyle. The memorial is flanked by a map room on one side, and a chapel on the other that memorializes the names of 3,095 missing from the two campaigns. A simple “Dedication Tablet” is mounted to the wall at the entrance to the chapel that reads:

1941 1945

IN PROUD REMEMBRANCE OF THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF HER SONS

AND IN HUMBLE TRIBUTE TO THEIR SACRIFICES

THIS MEMORIAL HAS BEEN ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

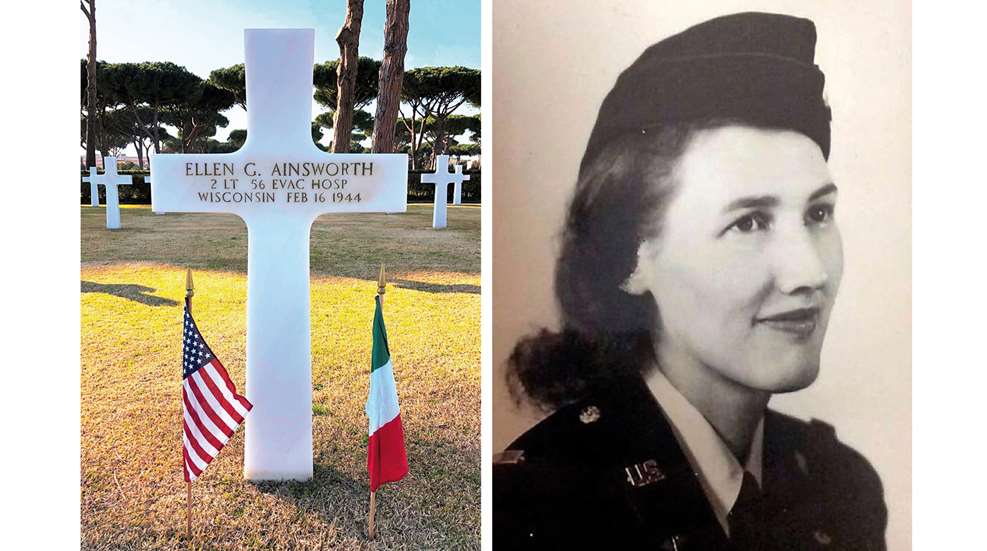

That tablet should include the word “daughters” as well, because 17 women are buried in the Sicily–Rome American Cemetery. Although their stories are all equally important, one of those women has been receiving some special attention lately, and that is for a very good reason.

Ellen Gertrude Ainsworth was born and raised in Glenwood City, Wisconsin. She graduated from Glenwood City High School in 1936 and, in 1941, the Eitel Hospital School of Nursing in Minneapolis. In March 1942 she enlisted in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps after which she served at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas and then Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Later that year Ainsworth was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and assigned to the 56thEvacuation Hospital before it departed for overseas in April 1943.

After landing at Casablanca, the 56th proceeded onward to the port of Bizerte in French Tunisia in June, and then to the beachhead at Paestum on the Gulf of Salerno, landing there on Sept. 26, 1943. 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth came ashore at Anzio/Nettuno on Jan. 25, 1944 and began treating the wounded just as the U.S. Army VI Corps was consolidating the beachhead there. Two weeks later, German artillery fire was falling on allied positions daily and the encampment of the 56th Evacuation Hospital was the target of a heavy barrage on Feb. 10 despite the Red Cross markings on the tents. At the height of the bombardment, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth was directing the removal of 42 surgical patients to an area of greater safety when a shell fragment struck her in the chest. Although she initially survived, Ainsworth succumbed to her wound six days later. She was just 24 years old, and she is the only Wisconsin servicewoman killed by enemy fire in the Second World War.

After her death, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth was automatically awarded the Purple Heart and, ultimately, the Silver Star with a citation reading in part: “By her disregard for her own safety and her calm assurance, she instilled confidence in her assistants and her patients, thereby preventing serious panic and injury.” In the early-50s, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth’s mother had the option of having her remains repatriated at government expense, but she chose to let her rest in the Italian soil where her life ended in 1944. She is still there today, less than three miles west of the spot where she suffered the wound that eventually caused her death. Back home, a building at the Wisconsin Veterans Home is named in her honor as is a conference room in the Pentagon and an Army Health Clinic at Fort Hamilton, New York. In Glenwood City, a bench at the High School athletic complex is dedicated to her and the local post office was named after her in 2016. While these honors are nothing trivial, there is a distinct possibility that she might eventually be awarded the greatest honor of them all. Recently an initiative to have 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth’s Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor has begun. If that initiative succeeds, she will be only the second woman to be awarded the medal.